Kashubian language

| Kashubian | |

|---|---|

| kaszëbsczi | |

| Native to | Poland |

| Region | Kashubia |

| Ethnicity | Kashubians and Poles |

Native speakers |

87,600 (2021 census) |

| Latin (Kashubian alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Officially recognized as of 2005, as a regional language, in some communes of Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland |

Recognised minority language in |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | csb |

| ISO 639-3 | csb |

| Glottolog | kash1274 |

| ELP | Kashubian |

| Linguasphere | 53-AAA-cb |

Kashubian or Cassubian (endonym: kaszëbsczi jãzëk, Polish: język kaszubski) is a West Slavic language belonging to the Lechitic subgroup along with Polish and Silesian. Although often classified as a language in its own right, it is mostly viewed as a dialect of Polish.

In Poland, it has been an officially recognized ethnic-minority language since 2005. Approximately 108,000 people use mainly Kashubian at home. It is the only remnant of the Pomeranian language. It is close to standard Polish with influence from Low German and the extinct Polabian (West Slavic) and Old Prussian (West Baltic) languages.

The Kashubian language exists in two different forms: vernacular dialects used in rural areas, and literary variants used in education.

Origin

Kashubian is assumed to have evolved from the language spoken by some tribes of Pomeranians called Kashubians, in the region of Pomerania, on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea between the Vistula and Oder rivers. It first began to evolve separately in the period from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century as the Polish-Pomeranian linguistic area began to divide based around important linguistic developments centred in the western (Kashubian) part of the area.

In the 19th century, Florian Ceynowa became Kashubian's first known activist. He undertook tremendous efforts to awaken Kashubian self-identity through the establishment of Kashubian language, customs, and traditions. He felt strongly that Poles were born brothers and that Kashubia was a separate nation.

The Young Kashubian movement followed in 1912, led by author and doctor Aleksander Majkowski, who wrote for the paper "Zrzësz Kaszëbskô" as part of the "Zrzëszincë" group. The group contributed significantly to the development of the Kashubian literary language.

The earliest printed documents in Polish with Kashubian elements date from the end of the 16th century. The modern orthography was first proposed in 1879.

Related languages

Many scholars and linguists debate whether Kashubian should be recognized as a Polish dialect or separate language. From the diachronic view it is a distinct Lechitic West Slavic language, but from the synchronic point of view it is a Polish dialect. Kashubian is closely related to Slovincian, while both of them are dialects of Pomeranian. Many linguists, in Poland and elsewhere, consider it a divergent dialect of Polish. Dialectal diversity is so great within Kashubian that a speaker of southern dialects has considerable difficulty in understanding a speaker of northern dialects. The spelling and the grammar of Polish words written in Kashubian, which is most of its vocabulary, is highly unusual, making it difficult for native Polish speakers to comprehend written text in Kashubian.

Like Polish, Kashubian includes about 5% loanwords from German (such as kùńszt "art"). Unlike Polish, these are mostly from Low German and only occasionally from High German. Other sources of loanwords include the Baltic languages.

Speakers

Poland

The number of speakers of Kashubian varies widely from source to source, ranging from as low as 4,500 to the upper 366,000. In the 2011 census, over 108,000 people in Poland declared that they mainly use Kashubian at home, of these only 10 percent consider Kashubian to be their mother tongue, with the rest considering themselves to be native speakers of both Kashubian and Polish. The number of people who can speak at least some Kashubian is higher, around 366,000. All Kashubian speakers are also fluent in Polish. A number of schools in Poland use Kashubian as a teaching language. It is an official alternative language for local administration purposes in Gmina Sierakowice, Gmina Linia, Gmina Parchowo, Gmina Luzino and Gmina Żukowo in the Pomeranian Voivodeship. Most respondents say that Kashubian is used in informal speech among family members and friends. This is most likely because Polish is the official language and spoken in formal settings.

Americas

During the Kashubian diaspora of 1855–1900, 115,700 Kashubians emigrated to North America, with around 15,000 emigrating to Brazil. Among the Polish community of Renfrew County, Ontario, Kashubian is widely spoken to this day, despite the use of more formal Polish by parish priests. In Winona, Minnesota, which Ramułt termed the "Kashubian Capital of America", Kashubian was regarded as "poor Polish," as opposed to the "good Polish" of the parish priests and teaching sisters. Consequently, Kashubian failed to survive Polonization and died out shortly after the mid-20th century.

Literature

Important for Kashubian literature was Xążeczka dlo Kaszebov by Florian Ceynowa (1817–1881). Hieronim Derdowski (1852–1902 in Winona, Minnesota) was another significant author who wrote in Kashubian, as was Aleksander Majkowski (1876–1938) from Kościerzyna, who wrote the Kashubian national epic The Life and Adventures of Remus. Jan Trepczyk was a poet who wrote in Kashubian, as was Stanisław Pestka. Kashubian literature has been translated into Czech, Polish, English, German, Belarusian, Slovene and Finnish. Aleksander Majkowski and Alojzy Nagel belong to the most commonly translated Kashubian authors of the 20th century. A considerable body of Christian literature has been translated into Kashubian, including the New Testament, much of it by Adam Ryszard Sikora (OFM). Franciszek Grucza graduated from a Catholic seminary in Pelplin. He was the first priest to introduce Catholic liturgy in Kashubian.

Works

The earliest recorded artifacts of Kashubian date back to the 15th century and include a book of spiritual psalms that were used to introduce Kashubian to the Lutheran church:

- 1586 Duchowne piesnie (Spiritual songs) D. Marcina Luthera y ynßich naboznich męzow. Zniemieckiego w Slawięsky ięzik wilozone Przes Szymana Krofea... w Gdainsku: przes Jacuba Rhode, Tetzner 1896: translated from pastorks. S. Krofeja, Słowińca (?) rodem z Dąbia.

- 1643 Mały Catechism (Little Catechism) D. Marciná Lutherá Niemiecko-Wándalski ábo Slowięski to jestá z Niemieckiego języká w Słowięski wystáwiony na jáwnosc wydan..., w Gdaińsku przes Jerzego Rhetá, Gdansk 1643. Pastor smołdziński ks. Mostnik, rodem ze Slupska.

- Perykopy smołdzinskie (Smoldzinski Pericope), published by Friedhelm Hinze, Berlin (East), 1967

- Śpiewnik starokaszubski (Old Kashubian songbook), published by Friedhelm Hinze, Berlin (East), 1967

Education

Throughout the communist period in Poland (1948-1989), Kashubian greatly suffered in education and social status. Kashubian was represented as folklore and prevented from being taught in schools. Following the collapse of communism, attitudes on the status of Kashubian have been gradually changing. It has been included in the program of school education in Kashubia although not as a language of teaching or as a required subject for every child, but as a foreign language taught 3 hours per week at parents' explicit request. Since 1991, it is estimated that there have been around 17,000 students in over 400 schools who have learned Kashubian. Kashubian has some limited usage on public radio and had on public television. Since 2005, Kashubian has enjoyed legal protection in Poland as an official regional language. It is the only language in Poland with that status, which was granted by the Act of 6 January 2005 on National and Ethnic Minorities and on the Regional Language of the Polish Parliament. The act provides for its use in official contexts in ten communes in which speakers are at least 20% of the population. The recognition means that heavily populated Kashubian localities have been able to have road signs and other amenities with Polish and Kashubian translations on them.

Dialects

Friedrich Lorentz wrote in the early 20th century that there were three main Kashubian dialects. These include the

- Northern Kashubian dialect

- Middle Kashubian dialect

- Southern Kashubian dialect

Other researches would argue that each tiny region of the Kaszuby has its own dialect, as in Dialects and Slang of Poland:

- Bylacki dialect

- Slowinski dialect

- Kabatkow dialect

- Zaborski dialect

- Tucholski and Krajniacki dialect (although both dialects would be considered a transitional form of the Wielkopolski dialect and are included as official Wielkopolskie dialects)

Features

A "standard" Kashubian language does not exist despite several attempts to create one; rather a diverse range of dialects takes its place. The vocabulary is heavily influenced by German and Polish and uses the Latin alphabet.

There are several similarities between Kashubian and Polish. For some linguists they consider this a sign that Kashubian is a dialect of Polish but others believe that this is just a sign that the two originate from the same location. They are nevertheless related to a certain degree and their proximity has made Kashubian influenced by Polish and its various dialects.

Exemplary differences between Kashubian and Polish:

- a consonant-softening outcome of Proto-Slavic soft syllabic r in northern Kashubian dialects: ex: Northern Kashubian: cwiardi, czwiôrtk; Polish: twardy, czwartek

- the disappearance of a movable e in the nominative case: ex: pòrénk, kóńc; poranek, koniec

- vowel ô takes the place of former long a, continuants of the old long a distinct from the old short a are present in most dialects of Polish but absent from the standard language

- transition of -jd- to -ńd- just like the Masurian dialects: ex: przińdą; przyjdą

Phonology and morphology

Kashubian makes use of simplex and complex phonemes with secondary place articulation /pʲ/, /bʲ/, /fʲ/, /vʲ/ and /mʲ/. They follow the Clements and Hume (1995) constriction model, where sounds are represented in terms of constriction. They are then organized according to particular features like anterior, implying the activation of features dominating it. Due to this model, the phonemes above are treated differently from the phonemes /p/, /b/, /f/, /v/ and /m/. The vocalic place node would be placed under the C-place node and V-place nodes interpolated to preserve well-forwardness.

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||

| Close | i | u | ||

| Close-mid | e | ə | o | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɞ | ɔ | |

| Open | a | |||

- The exact phonetic realization of the close-mid vowels /e, o/ depends on the dialect.

- Apart from these, there are also nasal vowels /ã, õ/. Their exact phonetic realization depends on the dialect.

Consonants

Kashubian has simple consonants with a secondary articulation along with complex ones with secondary articulation.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tʃ | (tɕ) | ||

| voiced | dz | dʒ | (dʑ) | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | (ɕ) | x |

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | (ʑ) | ||

| trill | (r̝) | |||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||

| Trill | r | |||||

- /tʃ, dʒ, ʃ, ʒ/ are palato-alveolar.

- /ɲ, tɕ, dʑ, ɕ, ʑ/ are alveolo-palatal; the last four appear only in some dialects.

- The fricative trill /r̝/ is now used only by some northern and northeastern speakers; other speakers realize it as flat postalveolar [ʐ].

- The labialized velar central approximant /w/ is realized as a velarized denti-alveolar lateral approximant [ɫ̪] by older speakers of southeastern dialects.

Stress

Among people who speak the northern dialects (including the extinct Slovincian dialect), the stress is free and partially mobile. Linguistic research on northern dialects is important for the reconstruction of the original stress in the Proto-Slavic, Proto-Balto-Slavic, and Proto-Indo-European languages.

A free, immobile stress (like in most Germanic and Romance languages, and in Greek) is representative for central dialects.

Speakers of southern dialects have a fixed initial accent (as in the Podhale Goral dialect).

Orthography

Kashubian alphabet

| Upper case | Lower case | Name of letters [2] | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | a | [a] |

| Ą | ą | ą | [õ], [ũ] |

| Ã | ã | ã | [ã], [ɛ̃] (Puck County, Wejherowo County) |

| B | b | bé | [b] |

| C | c | cé | [ts] |

| D | d | dé | [d] |

| E | e | e | [ɛ] |

| É | é | é | [e], [ɨj] in some dialects, [ɨ] at the end of a word, [i]/[ɨ] from Puck to Kartuzy |

| Ë | ë | szwa | [ə] |

| F | f | éf | [f] |

| G | g | gé | [ɡ] |

| H | h | ha | [x] |

| I | I | i | [i] |

| J | j | jot | [j] |

| K | k | ka | [k] |

| L | l | él | [l] |

| Ł | ł | éł | [w], [l] |

| M | m | ém | [m] |

| N | n | én | [n] |

| Ń | ń | éń | [ɲ], [n] |

| O | o | o | [ɔ] |

| Ò | ò | ò | [wɛ] |

| Ó | ó | ó | [o], [u] (southern dialects) |

| Ô | ô | ô |

[ɞ], [ɛ] (western dialects), [ɔ] (Wejherowo County), [o]/[u] (southern dialects)

[œ], [ø] (northern dialects) |

| P | p | pé | [p] |

| R | r | ér | [r] |

| S | s | és | [s] |

| T | t | té | [t] |

| U | u | u | [u] |

| Ù | ù | ù | [wʉ] |

| W | w | wé | [v] |

| Y | y | igrek | [i] |

| Z | z | zet | [z] |

| Ż | ż | żet | [ʒ], [ʑ] |

The following digraphs and trigraphs are used:

| Digraph | Phonemic value(s) |

|---|---|

| ch | /x/ |

| cz | /tʃ/, /tɕ/ |

| dz | /dz/ (/ts/) |

| dż | /dʒ/, /dʑ/ (/tʃ/, /tɕ/) |

| rz | /ʐ/ ~ /r̝/ (/ʂ/) |

| sz | /ʃ/, /ɕ/ |

Sample text

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Kashubian:

- Wszëtczi lëdze rodzą sã wòlny ë równy w swòji czëstnoce ë swòjich prawach. Mają òni dostóne rozëm ë sëmienié ë nôlégô jima pòstãpòwac wobec drëdzich w dëchù bracënotë.

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in English:

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Gallery

-

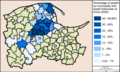

Percentage of people that speak Kashubian at home (2002)

Percentage of people that speak Kashubian at home (2002) -

-

-

Page of Stefan Ramułt Pomeranian (Kashubian language) Dictionary 1893

Page of Stefan Ramułt Pomeranian (Kashubian language) Dictionary 1893 -

Map showing regions in Poland where Kashubian is recognized as a regional language (orange) and where it could qualify in the upcoming years (yellow)

Map showing regions in Poland where Kashubian is recognized as a regional language (orange) and where it could qualify in the upcoming years (yellow) -

Church of the Pater Noster, Mount of Olives, Jerusalem. Lord's Prayer in Kashubian