Rice

Rice is a cereal grain, and in its domesticated form is the staple food for over half of the world's human population, particularly in Asia and Africa. Rice is the seed of the grass species Oryza sativa (Asian rice) or, much less commonly, O. glaberrima (African rice). Asian rice was domesticated in China some 13,500 to 8,200 years ago, while African rice was domesticated in Africa some 3,000 years ago.Rice has become commonplace in many cultures worldwide; in 2021, 787 million tons were produced, placing it third after sugarcane and maize. Only some 8% of rice is traded internationally. Three countries, China, India, and Indonesia together account for 59% of global consumption. Between 8% and 26% of the rice produced in developing nations is lost after harvest through factors such as poor transport and storage. Rice yields can be reduced by many pests including insects, rodents, and birds, as well as by weeds, and by diseases such as rice blast. Integrated pest management seeks to control damage from pests in a sustainable way.

Many varieties of rice have been bred to improve crop quality and productivity, and to provide desired texture, smell, and firmness. Biotechnology has created Green Revolution rice able to produce high yields when supplied with nitrogen fertilizer and managed intensively. Other products are rice able to express human proteins for medicinal use; flood-tolerant or deepwater rice; and drought-tolerant and salt-tolerant varieties. Rice is used as a model organism in biology.

Dry rice grain is milled to remove the outer layers; depending on how much is removed, products range from brown rice to rice with germ and white rice. Some is parboiled to make it easy to cook. Rice contains no gluten; it provides protein but not all the essential amino acids needed for good health. Rice of different types is eaten around the world. Long-grain rice tends to stay intact on cooking; medium-grain rice is stickier, and is used for sweet dishes, and in Italy for risotto; and sticky short-grain rice is used in Japanese sushi as it keeps its shape when cooked. White rice when cooked contains 29% carbohydrate and 2% protein, with some manganese. Golden rice is a variety produced by genetic engineering to contain vitamin A.

Production of rice is estimated to have caused over 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2022. Rice yields are predicted to fall by some 20% with each 1°C rise in global mean temperature. In human culture, rice plays a role in certain religions and popular beliefs, such as in weddings.

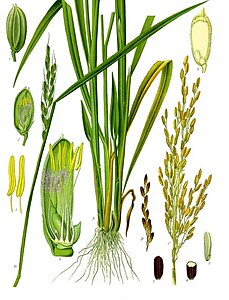

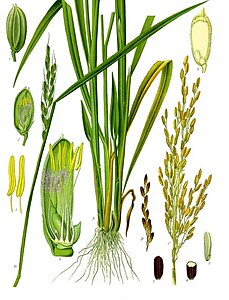

Description

The rice plant can grow to over 1 m (3 ft) tall; if in deep water, it can reach a length of 5 m (16 ft). A single plant may have several leafy stems or tillers. The upright stem is jointed with nodes along its length; a long slender leaf arises from each node. The self-fertile flowers are produced in a panicle, a branched inflorescence which arises from the last internode on the stem. There can be up to 350 spikelets in a panicle, each containing male and female flower parts (anthers and ovule). A fertilised ovule develops into the edible grain or caryopsis.

Rice is a cereal belonging to the family Poaceae. As a tropical crop, it can be grown during the two distinct seasons (dry and wet) of the year provided that sufficient water is made available. It is normally an annual, but in the tropics it can survive as a perennial, producing a ratoon crop.

-

-

Detail of rice plant showing flowers grouped in panicle. Male anthers protrude into the air where they can disperse their pollen.

Detail of rice plant showing flowers grouped in panicle. Male anthers protrude into the air where they can disperse their pollen.

Agronomy

Growing

Like all crops, rice depends for its growth on both biotic and abiotic environmental factors. The principal biotic factors are crop variety, pests, and plant diseases. Abiotic factors include the soil type, whether lowland or upland, amount of rain or irrigation water, temperature, day length, and intensity of sunlight.

Rice grains can be planted directly into the field where they will grow, or seedlings can be grown in a seedbed and transplanted into the field. Direct seeding needs some 60 to 80 kg of grain per hectare, while transplanting needs less, around 40 kg per hectare, but requires far more labour. Most rice in Asia is transplanted by hand. Mechanical transplanting takes less time but requires a carefully-prepared field and seedlings raised on mats or in trays to fit the machine. Rice does not thrive if continuously submerged. Rice can be grown in different environments, depending upon water availability. The usual arrangement is for lowland fields to be surrounded by bunds and flooded to a depth of a few centimetres until around a week before harvest time; this requires a large amount of water. The "alternate wetting and drying" technique uses less water. One form of this is to flood the field to a depth of 5 cm (2 in), then to let the water level drop to 15 cm (6 in) below surface level, as measured by looking into a perforated field water tube sunk into the soil, and then repeating the cycle. Deepwater rice varieties tolerate flooding to a depth of over 50 centimetres for at least a month. Upland rice is grown without flooding, in hilly or mountainous regions; it is rainfed like wheat or maize.

-

Ploughing a rice terrace with water buffaloes, Java

Ploughing a rice terrace with water buffaloes, Java -

Farmers planting rice by hand in Cambodia

Farmers planting rice by hand in Cambodia -

Mechanised rice planting in Japan

-

Ancient mountainside rice terraces at Banaue, Philippines

Ancient mountainside rice terraces at Banaue, Philippines

Harvesting

Across Asia, unmilled rice or "paddy" (Indonesian and Malay padi), is almost entirely the product of smallholder agriculture, and is often harvested manually. Larger farms make use of machines such as combine harvesters to reduce the input of labour. The grain is ready to harvest when the moisture content is 20–25%. Harvesting involves reaping, stacking the cut stalks, threshing to separate the grain, and cleaning by winnowing or screening. The rice grain is dried as soon as possible to bring the moisture content down to a level that is safe from mould fungi. Traditional drying relies on the heat of the sun, with the grain spread out on mats or on pavements.

-

Rice combine harvester in Chiba Prefecture, Japan

Rice combine harvester in Chiba Prefecture, Japan -

After the harvest, rice straw is gathered in the traditional way from small paddy fields in Mae Wang District, Thailand

After the harvest, rice straw is gathered in the traditional way from small paddy fields in Mae Wang District, Thailand -

-

Drying rice in Peravoor, India

Evolution

Phylogeny

The edible rice species are members of the BOP clade within the grass family, the Poaceae. The rice subfamily, Oryzoideae, is sister to the bamboos, Bambusoideae, and the cereal subfamily Pooideae. The rice genus Oryza is one of eleven in the Oryzeae; it is sister to the Phyllorachideae. The edible rice species O. sativa, and O. glaberrima are among some 300 species or subspecies in the genus.

| Poaceae |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

Oryza sativa rice was first domesticated in the Yangtze River basin in China 13,500 to 8,200 years ago. The functional allele for nonshattering, the critical indicator of domestication in grains, as well as five other single-nucleotide polymorphisms, is identical in both indica and japonica. This implies a single domestication event for O. sativa. Both indica and japonica forms of Asian rice sprang from a single domestication event in China from the wild rice Oryza rufipogon. Despite this evidence, it appears that indica rice arose when japonica arrived in India about 4,500 years ago and hybridised with another rice, whether an undomesticated proto-indica or wild O. nivara.

Cultivation, migration and trade spread rice around the world—first to much of east Asia, then further abroad, and eventually to the Americas as part of the Columbian exchange after 1492. The now less common Oryza glaberrima (African rice) was independently domesticated in Africa around 3,000 years ago, and introduced to the Americas by the Spanish.

Commerce

| Rice production – 2021 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Millions of tonnes |

| China | 213 |

| India | 195 |

| Bangladesh | 57 |

| Indonesia | 54 |

| Vietnam | 44 |

| Thailand | 30 |

| World | 787 |

Production

In 2021, world production of rice was 787 million tonnes, led by China and India with a combined 52% of the total. This placed rice third in the list of crops by production, after sugarcane and maize. Other major producers were Bangladesh, Indonesia and Vietnam. 90% of world production is from Asia.

-

![Production of rice (2021)[21]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/82/Production_of_rice_%282019%29.svg/499px-Production_of_rice_%282019%29.svg.png) Production of rice (2021)

Production of rice (2021) -

Rice's share (orange) of world crop production fell in the 21st century.

Rice's share (orange) of world crop production fell in the 21st century.

Food security

Rice is a major food staple in Asia, Latin America, and some parts of Africa, feeding over half of the world's population. Many rice grain producing countries have significant losses post-harvest at the farm and because of poor roads, inadequate storage technologies, inefficient supply chains and farmer's inability to bring the produce into retail markets dominated by small shopkeepers. A World Bank – FAO study states that 8% to 26% of rice is lost in developing nations, on average, every year, because of post-harvest problems and poor infrastructure. Farmers in developing countries such as China, India and others lose approximately US$89 billion of income in preventable post-harvest farm losses, poor transport, the lack of proper storage and retail. A 2007 study states that if these post-harvest grain losses could be eliminated with better infrastructure and retail network, in India alone enough food would be saved every year to feed 70 to 100 million people.

Processing

The dry grain is milled to remove the outer layers, namely the husk and bran. These can be removed in a single step, in two steps, or as in commercial milling in a multi-step process of cleaning, dehusking, separation, polishing, grading, and weighing. Brown rice only has the inedible chaff removed. Further milling removes bran and the germ to create successively whiter products. In some countries, a popular form, parboiled rice (also known as converted rice and easy-cook rice) is subjected to a steaming or parboiling process while still a brown rice grain. The parboil process causes a gelatinisation of the starch in the grains. The grains become less brittle, and the color of the milled grain changes from white to yellow. The rice is then dried, and can then be milled as usual or used as brown rice. Milled parboiled rice is nutritionally superior to standard milled rice, because the process causes nutrients from the outer husk (especially thiamine) to move into the endosperm, so that less is lost when the husk is polished off during milling. Raw rice may be ground into flour for many uses, including making beverages such as amazake, horchata, rice milk, and rice wine. Rice does not contain gluten, so is suitable for people on a gluten-free diet. Rice is a good source of protein and a staple food in many parts of the world, but it is not a complete protein: it does not contain all of the essential amino acids in sufficient amounts for good health.

-

Rice processing removes one or more layers to create marketable products.

Rice processing removes one or more layers to create marketable products.

A: Rice with chaff

B: Brown rice

C: Rice with germ

D: White rice with bran residue

E: Polished

(1): Chaff

(2): Bran

(3): Bran residue

(4): Cereal germ

(5): Endosperm -

Trade and distribution

World trade figures are much smaller than those for production, as less than 8% of rice produced is traded internationally. Developing countries are the main players in the world rice trade, accounting for 83% of exports and 85% of imports. While there are numerous importers of rice, the exporters of rice are limited. Five countries—Thailand, Vietnam, China, the United States and India—in decreasing order of exported quantities, accounted for about three-quarters of world rice exports in 2002. However, this ranking has been rapidly changing in recent years. In 2010, the three largest exporters of rice, in decreasing order of quantity exported were Thailand, Vietnam and India. By 2012, India became the largest exporter of rice with a 100% increase in its exports on year-to-year basis, and Thailand slipped to third position. Together, Thailand, Vietnam and India accounted for nearly 70% of the world rice exports.

The primary variety exported by Thailand and Vietnam were Jasmine rice, while exports from India included aromatic Basmati variety. China, an exporter of rice in the early 2000s, had become a net importer of rice by 2010. According to a USDA report, the world's largest exporters of rice in 2012 were India (9.75 million metric tons (10.75 million short tons)), Vietnam (7 million metric tons (7.7 million short tons)), Thailand (6.5 million metric tons (7.2 million short tons)), Pakistan (3.75 million metric tons (4.13 million short tons)) and the United States (3.5 million metric tons (3.9 million short tons)).

Yield records

The average world yield for rice was 4.3 metric tons per hectare (1.9 short tons per acre), in 2010. Australian rice farms were the most productive in 2010, with a nationwide average of 10.8 metric tons per hectare (4.8 short tons per acre).

Yuan Longping of China's National Hybrid Rice Research and Development Center set a world record for rice yield in 2010 at 19 metric tons per hectare (8.5 short tons per acre) on a demonstration plot. These efforts employed specially developed rice breeds and System of Rice Intensification (SRI), an innovation in rice farming.

Worldwide consumption

As of 2016, the countries with the highest national consumption were China (29% of total), India, and Indonesia, together comprising 59% of total world consumption. On an annual average from 2020-23, China consumed 154 million tonnes of rice, India consumed 109 million tonnes, and Bangladesh and Indonesia consumed about 36 million tonnes each.

Per capita in 2016, the highest levels of rice consumption were in Myanmar (306 kg per year), Vietnam (285 kg), Thailand (233 kg), Bangladesh (229 kg), and Indonesia (210 kg), while the average per capita consumption of rice among all countries was 72 kg per year.

Food

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 544 kJ (130 kcal) |

28.6 g |

|

0.2 g |

|

2.4 g |

|

| Vitamins |

Quantity

%DV†

|

| Thiamine (B1) |

2% 0.02 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

2% 0.02 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

3% 0.4 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

8% 0.41 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

4% 0.05 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

1% 2 μg |

| Minerals |

Quantity

%DV†

|

| Calcium |

0% 3 mg |

| Iron |

2% 0.2 mg |

| Magnesium |

4% 13 mg |

| Manganese |

18% 0.38 mg |

| Phosphorus |

5% 37 mg |

| Potassium |

1% 29 mg |

| Sodium |

0% 0 mg |

| Zinc |

4% 0.4 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 69 g |

|

| |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

Rice is commonly consumed as food around the world. The varieties of rice are typically classified as long-, medium-, and short-grained. The grains of long-grain rice (high in amylose) tend to remain intact after cooking; medium-grain rice (high in amylopectin) becomes more sticky. Medium-grain rice is used for sweet dishes, for risotto in Italy, and many rice dishes, such as arròs negre, in Spain. Some varieties of long-grain rice that are high in amylopectin, known as Thai Sticky rice, are usually steamed. A stickier short-grain rice is used for sushi; the stickiness allows rice to hold its shape when cooked. Short-grain rice is used extensively in Japan, including to accompany savoury dishes.

Nutrition

Cooked white rice is 69% water, 29% carbohydrates, 2% protein, and contains negligible fat (table). In a reference serving of 100 grams (3.5 oz), cooked white rice provides 130 calories of food energy, and contains moderate levels of manganese (18% DV), with no other micronutrients in significant content (all less than 10% of the Daily Value).

In 2018, the World Health Organization recommended fortifying rice with micronutrients, particularly iron to improve hemoglobin levels in anemic children. A 2022 review of storage and cooking methods on iron-fortified rice found that use of ferric pyrophosphate for iron fortification provided rice with organoleptic qualities and consumer acceptance similar to those of unfortified milled rice.

Golden rice

Golden rice is a variety produced through genetic engineering to biosynthesize beta-carotene, a precursor of vitamin A, in the edible parts of the rice. It is intended to produce a fortified food to be grown and consumed in areas with a shortage of dietary vitamin A. Vitamin A deficiency causes xerophthalmia, a range of eye conditions including permanent blindness, and increases risk of mortality from measles and diarrhea in children. In 2013, the prevalence of deficiency was high in sub-Saharan Africa (48%; 25–75), and South Asia (44%; 13–79). Golden rice has been opposed by environmental and anti-globalisation activists. In 2016 more than 100 Nobel laureates encouraged the use of a strain with a raised beta-carotene content on the grounds that this would alleviate vitamin A deficiency in Africa and Asia.

Rice and climate change

Greenhouse gases from rice

In 2022, greenhouse gas emissions from rice cultivation were estimated at 5.7 billion tonnes CO2eq, representing 1.2% of total emissions. Within the agriculture sector, rice produces almost half the greenhouse gas emissions from croplands, and some 30% of agricultural methane emissions and 11% of agricultural nitrous oxide emissions. Methane is released from rice fields subject to long-term flooding, as this inhibits the soil from absorbing atmospheric oxygen, resulting in anaerobic fermentation of organic matter in the soil. Emissions can be limited by planting new varieties, not flooding continuously, and removing straw.

Effect of global warming on rice

A 2010 study found that, as a result of rising temperatures and decreasing solar radiation during the later years of the 20th century, the rice yield, measured at over 200 farms in seven Asian countries, decreased by between 10% and 20%. This may be caused by increased night-time respiration. IRRI has predicted that Asian rice yields will fall by some 20% per 1°C rise in global mean temperature. Further, rice is unable to yield grain if the flowers experience a temperature of 35°C or more for over one hour, so the crop would be lost under these conditions.

Pests, weeds, and diseases

Rice pests are animals which have the potential to reduce the yield or value of the rice crop (or of rice seeds); plants which do this are described as weeds, while microbes are described as pathogens, disease-causing organisms. Rice pests include insects, nematodes, rodents, and birds. A variety of factors can contribute to pest outbreaks, including climatic factors, improper irrigation, the overuse of insecticides and high rates of nitrogen fertilizer application. Weather conditions also contribute to pest outbreaks. For example, rice gall midge and army worm outbreaks tend to follow periods of high rainfall early in the wet season, while thrips outbreaks are associated with drought.

Pests and weeds

(Oxya chinensis)

Borneo, Malaysia

Major rice insect pests include: the brown planthopper, several species of stemborers—including those in the genera Scirpophaga and Chilo, the rice gall midge, rice bugs, notably in the genus Leptocorisa, defoliators such as the rice leafroller, hispa, and grasshoppers. The fall armyworm moth causes damage to rice crops.

Several nematode species infect rice crops, causing diseases such as ufra (Ditylenchus dipsaci), white tip disease (Aphelenchoide bessei), and root knot disease (Meloidogyne graminicola). Some nematode species such as Pratylenchus spp. are most damaging to upland rice. Rice root nematode (Hirschmanniella oryzae) is a migratory endoparasite which on higher inoculum levels leads to complete destruction of a rice crop. Beyond being obligate parasites, they decrease the vigor of plants and increase the plants' susceptibility to other pests and diseases. Other harmful organisms include panicle rice mite, rats, and the weed Echinochloa crus-galli. Rice may be infested by the hemiparasitic eudicot weed Striga hermonthica.

Diseases

Rice blast, caused by the fungus Magnaporthe grisea (syn. M. oryzae, Pyricularia oryzae), is the most significant disease affecting rice cultivation. It and bacterial leaf streak (caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae) are perennially the two worst rice diseases worldwide; they are both among the worst 10 diseases of all plants. Other major fungal and bacterial rice diseases include sheath blight (caused by Rhizoctonia solani), false smut (Ustilaginoidea virens), bacterial panicle blight (Burkholderia glumae), sheath rot (Sarocladium oryzae), and bakanae (Fusarium fujikuroi). Viral diseases include rice bunchy stunt, rice dwarf, rice tungro, and rice yellow mottle. An ascomycete fungus, Cochliobolus miyabeanus, causes brown spot disease in rice.

Integrated pest management

Crop protection scientists are trying to develop rice pest management techniques which are sustainable, in other words, to manage crop pests in such a manner that future crop production is not threatened. Sustainable pest management is based on four principles: biodiversity, host plant resistance, landscape ecology, and hierarchies in a landscape—from biological to social. At present, rice pest management includes cultural techniques, pest-resistant rice varieties, and pesticides (which include insecticide). Increasingly, there is evidence that farmers' pesticide applications are often unnecessary, and even facilitate pest outbreaks. By reducing the populations of natural enemies of rice pests, misuse of insecticides can actually lead to pest outbreaks. The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) demonstrated in 1993 that an 87.5% reduction in pesticide use can lead to an overall drop in pest numbers. IRRI conducted campaigns in 1994 and 2003 which discouraged insecticide misuse and promoted smarter pest management in Vietnam.

Rice plants produce their own chemical defenses to protect themselves from pest attacks. Some synthetic chemicals, such as the herbicide 2,4-D, cause the plant to increase the production of certain defensive chemicals and thereby increase the plant's resistance to some types of pests. Conversely, other chemicals, such as the insecticide imidacloprid, can induce changes in the gene expression of the rice that cause the plant to become more susceptible to attacks by certain types of pests.

Botanicals or "natural pesticides" are used by some farmers in an attempt to control rice pests. Botanicals include extracts of leaves, or a mulch of the leaves themselves. Some upland rice farmers in Cambodia spread chopped leaves of the bitter bush (Chromolaena odorata) over the surface of fields after planting. This practice may help the soil retain moisture and thereby facilitate seed germination. Farmers believe that the leaves are a natural fertilizer and help suppress weed and insect infestations.

Among rice cultivars, there are differences in the responses to, and recovery from, pest damage. Many rice varieties have been selected for resistance to insect pests. Therefore, particular cultivars are recommended for areas prone to certain pest problems. The genetically based ability of a rice variety to withstand pest attacks is called resistance. Three main types of plant resistance to pests are recognized as nonpreference, antibiosis, and tolerance. Nonpreference (or antixenosis) describes host plants which insects prefer to avoid; antibiosis is where insect survival is reduced after the ingestion of host tissue; and tolerance is the capacity of a plant to produce high yield or retain high quality despite insect infestation.

Ecotypes and cultivars

While most rice is bred for crop quality and productivity, there are varieties selected for characteristics such as texture, smell, and firmness. There are four major categories of rice worldwide: indica, japonica, aromatic and glutinous. The different varieties of rice are not considered interchangeable, either in food preparation or agriculture, so as a result, each major variety is a completely separate market from other varieties. It is common for one variety of rice to rise in price while another one drops in price.

Rice cultivars also fall into groups according to environmental conditions, season of planting, and season of harvest, called ecotypes. Some major groups are the Japan-type (grown in Japan), "buly" and "tjereh" types (Indonesia); sali (or aman—main winter crop), ahu (also aush or ghariya, summer), and boro (spring) (Bengal and Assam).

The International Rice Research Institute is in the Philippines, with over 100,000 rice accessions held in the International Rice Genebank. Rice cultivars are often classified by their grain shapes and texture. For example, much of southeast Asia grows sticky or glutinous rice (which means sticky, not high in gluten). High-yield cultivars of rice suitable for cultivation in Africa and other dry ecosystems, called the new rice for Africa (NERICA) cultivars, have been developed to improve food security in West Africa. Draft genomes for the two most common rice cultivars, indica and japonica, were published in April 2002. Rice was chosen as a model organism for the biology of grasses because of its relatively small genome (~430 megabase pairs). Rice was the first crop with a complete genome sequence. Since then, the genomes of hundreds of accessions comprising both cultivated and wild species of Asian and African rice have been sequenced.

Biotechnology

High-yielding varieties

The high-yielding varieties are a group of crops created during the Green Revolution to increase global food production. This project enabled labor markets in Asia to shift away from agriculture, and into industrial sectors. The first "Rice Car", IR8, was produced in 1966 at the International Rice Research Institute through a cross between an Indonesian variety named "Peta" and a Chinese variety named "Dee Geo Woo Gen". Green Revolution varieties were bred to have short strong stems. This was found to have involved genetic changes that disrupted the gibberellin signaling pathway. Photosynthetic investment in the stem is reduced dramatically as the shorter plants are inherently more stable mechanically. Food is redirected to grain production, amplifying the effect of chemical fertilizers on commercial yield. In the presence of nitrogen fertilizers, and intensive crop management, these varieties increase their yield two to three times.

Expression of human proteins

Ventria Bioscience has genetically modified rice to express lactoferrin, lysozyme which are proteins usually found in breast milk, and human serum albumin. These proteins have antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal effects. Rice containing these added proteins can be used as a component in oral rehydration solutions to treat diarrheal diseases, thereby shortening their duration and reducing recurrence. Such supplements may also help reverse anemia.

Flood-tolerant rice

Due to the varying levels that water can reach in regions of cultivation, flood tolerant varieties have long been developed and used. Flooding is an issue that many rice growers face, especially in South and South East Asia where flooding annually affects 20 million hectares (49 million acres). Flooding has historically led to massive losses in yields, such as in the Philippines, where in 2006, rice crops worth $65 million were lost to flooding. Standard rice varieties cannot withstand stagnant flooding for more than about a week, since it disallows the plant access to necessary requirements such as sunlight and gas exchange. The Swarna Sub1 cultivar can tolerate week-long submergence, consuming carbohydrates efficiently and continuing to grow.

Drought-tolerant rice

Drought represents a significant environmental stress for rice production, with 19–23 million hectares (47–57 million acres) of rainfed rice production in South and South East Asia often at risk. Under drought conditions, without sufficient water to afford them the ability to obtain the required levels of nutrients from the soil, conventional commercial rice varieties can be severely affected—for example, yield losses as high as 40% have affected some parts of India, with resulting losses of around US$800 million annually.

The International Rice Research Institute conducts research into developing drought-tolerant rice varieties, including the varieties 5411 and Sookha dhan, currently being employed by farmers in the Philippines and Nepal respectively. In addition, in 2013 the Japanese National Institute for Agrobiological Sciences led a team which successfully inserted the DEEPER ROOTING 1 (DRO1) gene, from the Philippine upland rice variety Kinandang Patong, into the popular commercial rice variety IR64, giving rise to a far deeper root system in the resulting plants. This facilitates an improved ability for the rice plant to derive its required nutrients in times of drought via accessing deeper layers of soil, a feature demonstrated by trials which saw the IR64 + DRO1 rice yields drop by 10% under moderate drought conditions, compared to 60% for the unmodified IR64 variety.

Salt-tolerant rice

Soil salinity poses a major threat to rice crop productivity, particularly along low-lying coastal areas during the dry season. For example, roughly 1 million hectares (2.5 million acres) of the coastal areas of Bangladesh are affected by saline soils. These high concentrations of salt can severely affect rice plants' physiology, especially during early stages of growth, and as such farmers are often forced to abandon these areas.

Progress has been made, however, in developing rice varieties capable of tolerating such conditions; the hybrid created from the cross between the commercial rice variety IR56 and the wild rice species Oryza coarctata is one example. O. coarctata can grow in soils with double the limit of salinity of normal varieties, but does not produce edible rice. Developed by the International Rice Research Institute, the hybrid variety utilises specialised leaf glands that remove salt into the atmosphere. It was produced from one successful embryo out of 34,000 crosses between the two species; this was then backcrossed to IR56 with the aim of preserving the genes responsible for salt tolerance that were inherited from O. coarctata.

Environment-friendly rice

Producing rice in paddies is harmful for the environment due to the release of methane by methanogenic bacteria. These bacteria live in the anaerobic waterlogged soil, consuming nutrients released by rice roots. Putting the barley gene SUSIBA2 into rice creates a shift in biomass production from root to shoot, decreasing the methanogen population, and resulting in a reduction of methane emissions of up to 97%. Further, the modification increases the amount of rice grains.

Model organism

Rice is used as a model organism for investigating the molecular mechanisms of meiosis and DNA repair in higher plants. Meiosis is a key stage of the sexual cycle in which diploid cells in the ovule (female structure) and the anther (male structure) produce haploid cells that develop further into gametophytes and gametes. So far, 28 meiotic genes of rice have been characterized. Studies of rice gene OsRAD51C showed that this gene is necessary for homologous recombinational repair of DNA, particularly the accurate repair of DNA double-strand breaks during meiosis. Rice gene OsDMC1 was found to be essential for pairing of homologous chromosomes during meiosis, and rice gene OsMRE11 was found to be required for both synapsis of homologous chromosomes and repair of double-strand breaks during meiosis.

In human culture

Rice plays an important role in certain religions and popular beliefs. In many cultures, relatives scatter rice over the bride and groom in a wedding ceremony. In Malay weddings, rice features in multiple special wedding foods such as "sweet glutinous rice, buttered rice, [and] yellow glutinous rice". The pounded rice ritual is conducted during weddings in Nepal. The bride gives a leafplate full of pounded rice to the groom after he requests it politely from her. In the Philippines rice wine, tapuy, is used for weddings, rice harvesting ceremonies and other celebrations. Dewi Sri is the traditional rice goddess of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese people in Indonesia. Most rituals involving Dewi Sri are associated with the mythical origin attributed to the rice plant, the staple food of the region. A 2014 study of Han Chinese communities found that a history of farming rice makes cultures more psychologically interdependent, whereas a history of farming wheat makes cultures more independent. A Royal Ploughing Ceremony is held in certain Asian countries to mark the beginning of the rice planting season. It is still honored in the kingdoms of Cambodia and Thailand. The 2,600-year-old tradition – begun by Śuddhodana in Kapilavastu – was revived in the republic of Nepal in 2017 after a lapse of a few years. The Thai kings have patronised rice breeding since at least the reign of Chulalongkorn, and his great-great-grandson Vajiralongkorn released five particular rice varieties to celebrate his coronation.

![Production of rice (2021)[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/82/Production_of_rice_%282019%29.svg/499px-Production_of_rice_%282019%29.svg.png)