Arch

An arch is a curved vertical structure spanning an open space underneath it. Arch can either support the load above it or perform a purely decorative role. The arch dates back to fourth millennium BC, but became popular only after its adoption by the Romans in the 4th century BC. In much of the world introduction of the arch was a result of European influence.

Arch-like structures can be horizontal, like an arch dam that withstands the horizontal hydrostatic pressure load. Arches are used as supports for many types of vaults, with the barrel vault in particular being a continuous arch.

Basic concepts

Terminology

A true arch is a load-bearing arc with elements held together by compression. The term false arch has two meanings. It is usually used to designate an arch that has no structural purpose, like a proscenium arch in theaters used to frame the performance for the spectators, but is also applied to corbelled and triangular arches that are not based on compression.

A typical true masonry arch consists of the following elements:

- Keystone, the top block in an arch. Portion of the arch around the keystone (including the keystone itself), with no precisely defined boundary, is called a crown

- Voussoir (a wedge-like construction block)

- Extrados (external surface of the arch)

- Impost is block at the base of the arch (the voussoir immediately above the impost is a springer). The tops of imposts define the springing level. A portion of the arch between the springing level and the crown (centered around the 45° angle) is called a haunch. If the arch resides on top of a column, the impost is formed by an abacus or its thicker version, dosseret.

- Intrados (underside of the arch, also known as a soffit)

- Rise (height of the arc, distance from the springing level to the crown)

- Clear span

- Abutment The triangular-shaped portion of the wall between the extrados and the horizontal division above is called spandrel.

A (left or right) half-segment of an arch is called an arc, the overall line of an arch is arcature (this term is also used for an arcade). Archivolt is the exposed (front-facing) part of the arch, sometimes decorated (occasionally also used to designate the intrados).

Arch action

A true arch, due to its rise, resolves the vertical loads into horizontal and vertical reactions at the ends, a so called arch action. The vertical load produces a positive bending moment in the arch, while the inward-directed horizontal reaction from the spandrel/abutment provides a counterbalancing negative moment. As a result, the bending moment in any segment of the arch is much smaller than in a beam with the equivalent load and span. The diagram on the right shows the difference between loaded arch and beam. Elements of the arch are mostly subject to compression (A), while in the beam a bending moment is present, with compression at the top and tension at the bottom (B).

Arrangements

A sequence of arches can be grouped together forming an arcade. Romans perfected this form, as shown, for example, by arched structures of Pont du Gard.

An opening of the arch can be filled, creating a blind arch. Blind arches are frequently decorative, and were extensively used in Early Christian, Romanesque, and Islamic architecture. Alternatively, the opening can be filled with smaller arches, producing a containing arch, common in Gothic and Romanesque architecture. Multiple arches can be superimposed with an offset, creating an interlaced series of usually (with some exceptions) blind and decorative arches. Most likely of Islamic origin, the interlaced arcades were popular in Romanesque and Gothic architecture.

-

Arcades of Pont du Gard (Roman)

Arcades of Pont du Gard (Roman) -

Large blind arch containing three smaller blind arches

Large blind arch containing three smaller blind arches -

Interlaced arcade of blind arches at Castle Acre (Romanesque)

Interlaced arcade of blind arches at Castle Acre (Romanesque) -

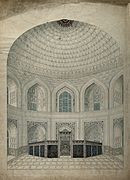

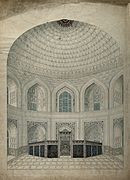

Blind arches inside Dome of the Rock (Islamic)

Blind arches inside Dome of the Rock (Islamic)

Structural

Structurally, the relieving arches can be used to take off load from some portions of the building (for example, to allow use of thinner exterior walls with larger window openings, or, like in Roman Pantheon, to redirect the weight of the upper structures to particular strong points). Transverse arches, introduced in Carolingian architecture, are placed across the nave to compartmentalize the internal space into bays and support vaults. Diaphragm arch similarly goes in the transverse direction, but carries a section of wall on top. It is used to support or divide sections of the high roof. The strainer arches were built as an afterthought to prevent two adjacent supports from imploding due to miscalculation. Frequently they were made very decorative, with one of the best examples provided by the Wells Cathedral.

-

Brick relieving arches at Pantheon (Roman)

Brick relieving arches at Pantheon (Roman) -

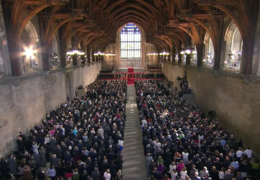

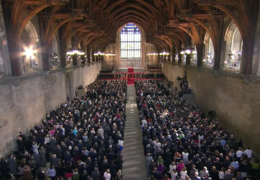

Transverse arches in Speyer Cathedral

Transverse arches in Speyer Cathedral -

Diaphragm arch in San Miniato al Monte

Diaphragm arch in San Miniato al Monte -

Elaborate "scissors" strainer arch in Wells Cathedral

Elaborate "scissors" strainer arch in Wells Cathedral

Shapes

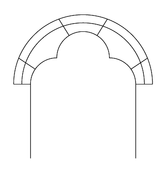

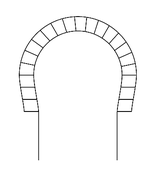

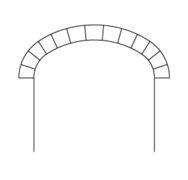

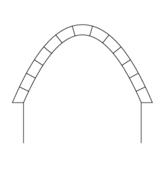

The large variety of arch shapes (left) can mostly be classified into three broad categories: rounded, pointed, and parabolic.

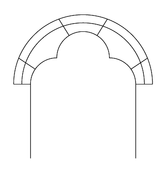

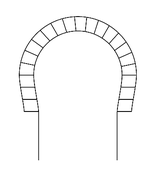

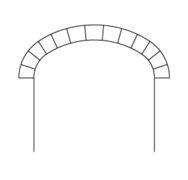

Rounded

"Round" semicircular arches were commonly used for ancient arches that were constructed of heavy masonry, and were relied heavily on by the Roman builders since the 4th century BC. It is considered to be the most common arch form.

A segmental arch, with a rounded shape that is less than a semicircle, is very old (the versions were cut in the rock in Ancient Egypt c. 2100 BC at Beni Hasan). Since then it was occasionally used in Greek temple and Islamic, got popular as window pediments during the Renaissance.

A basket arch (also known as depressed arch, chop arch, drop arch, three-centred arch, basket handle arch) consists of segments of three circles with origins at three different centers). Was used in late Gothic and Baroque architecture.

A horseshoe arch (also known as keyhole arch) has a rounded shape that includes more than a semicircle, originates in Islamic architecture and was known in areas of Europe with Islamic influence (Spain, Southern France, Italy). Occasionally used in Gothics, it briefly enjoyed popularity as the entrance door treatment in the interwar England.

-

-

Segmental arch of the Alconétar Bridge

-

Bridge with a basket handle arch

Bridge with a basket handle arch -

Pointed

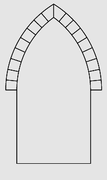

A pointed arch consists of two or more circle segments culminating in a point at the top. It originated in the Islamic architecture, arrived in Europe in the second half of the 11th century (Cluny Abbey) and later became prominent in the Gothic architecture. The advantages of a pointed arch over a semicircular one are flexible ratio of span to rise and lower horizontal reaction at the base. This innovation allowed for taller and more closely spaced openings, which are typical of Gothic architecture.

-

Pointed arches of Mosque of Ibn Tulun (9th century AD)

Pointed arches of Mosque of Ibn Tulun (9th century AD)

Parabolic

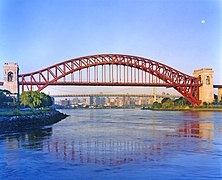

The parabolic arch employs the principle that when weight is uniformly applied to an arch, the internal compression resulting from that weight will follow a parabolic profile. Of all forms of arch, the parabolic arch produces the most thrust at the base yet can span the greatest distances. It is commonly used in bridges, where long spans are needed.

The catenary arch has a different shape from the parabolic arch. Being the shape of the curve that a loose span of chain or rope traces, the catenary is the structurally ideal shape for a freestanding arch of constant thickness.

Other

Forms of arch displayed chronologically, roughly in chronological order of development:

-

Triangular arch

Triangular arch -

Round or semicircular arch

Round or semicircular arch -

Segmental arch (less than a semicircle)

Segmental arch (less than a semicircle) -

Unequal round or rampant arch

Unequal round or rampant arch -

-

-

Shouldered flat arch (see also jack arch)

Shouldered flat arch (see also jack arch) -

Trefoil or three-foiled cusped arch

Trefoil or three-foiled cusped arch -

-

Three-centered arch

Three-centered arch -

Elliptical arch

Elliptical arch -

-

-

Reverse ogee arch

Reverse ogee arch -

Four-centred or Tudor arch

Four-centred or Tudor arch -

Hinged arches

The practical arch bridges are built either as a fixed arch, a two-hinged arch, or a three-hinged arch. The fixed arch is most often used in reinforced concrete bridges and tunnels, which have short spans. Because it is subject to additional internal stress from thermal expansion and contraction, this kind of arch is statically indeterminate (the internal state is impossible to determine based on the external forces alone).

The two-hinged arch is most often used to bridge long spans. This kind of arch has pinned connections at its base. Unlike that of the fixed arch, the pinned base can rotate, thus allowing the structure to move freely and compensate for the thermal expansion and contraction that changes in outdoor temperature cause. However, this can result in additional stresses, and therefore the two-hinged arch is also statically indeterminate, although not as much as the fixed arch.

The three-hinged arch is not only hinged at its base, like the two-hinged arch, yet also at its apex. The additional apical connection allows the three-hinged arch to move in two opposite directions and compensate for any expansion and contraction. This kind of arch is thus not subject to additional stress from thermal change. Unlike the other two kinds of arch, the three-hinged arch is therefore statically determinate. It is most often used for spans of medial length, such as those of roofs of large buildings. Another advantage of the three-hinged arch is that the reaction of the pinned bases is more predictable than the one for the fixed arch, allowing shallow, bearing-type foundations in spans of medial length. In the three-hinged arch "thermal expansion and contraction of the arch will cause vertical movements at the peak pin joint but will have no appreciable effect on the bases," which further simplifies foundational design.

History

Bronze Age: ancient Near East

True arches, as opposed to corbel arches, were known by a number of civilizations in the ancient Near East including the Levant, but their use was infrequent and mostly confined to underground structures, such as drains where the problem of lateral thrust is greatly diminished. An example of the latter would be the Nippur arch, built before 3800 BC, and dated by H. V. Hilprecht (1859–1925) to even before 4000 BC. Rare exceptions are an arched mudbrick home doorway dated to c. 2000 BC from Tell Taya in Iraq and two Bronze Age arched Canaanite city gates, one at Ashkelon (dated to c. 1850 BC), and one at Tel Dan (dated to c. 1750 BC), both in modern-day Israel. An Elamite tomb dated 1500 BC from Haft Teppe contains a parabolic vault which is considered one of the earliest evidences of arches in Iran.

Classical Persia and Greece

In ancient Persia, the Achaemenid Empire (550 BC–330 BC) built small barrel vaults (essentially a series of arches built together to form a hall) known as iwan, which became massive, monumental structures during the later Parthian Empire (247 BC–AD 224). This architectural tradition was continued by the Sasanian Empire (224–651), which built the Taq Kasra at Ctesiphon in the 6th century AD, the largest free-standing vault until modern times.

An early European example of a voussoir arch appears in the 4th century BC Greek Rhodes Footbridge.

Ancient Rome

The ancient Romans learned the arch from the Etruscans, refined it and were the first builders in Europe to tap its full potential for above ground buildings:

The Romans were the first builders in Europe, perhaps the first in the world, to fully appreciate the advantages of the arch, the vault and the dome.

Throughout the Roman empire, their engineers erected arch structures such as bridges, aqueducts, and gates. They also introduced the triumphal arch as a military monument. Vaults began to be used for roofing large interior spaces such as halls and temples, a function that was also assumed by domed structures from the 1st century BC onwards.

The segmental arch was first built by the Romans who realized that an arch in a bridge did not have to be a semicircle, such as in Alconétar Bridge or Ponte San Lorenzo. They were also routinely used in house construction, as in Ostia Antica (see picture).

Ancient China

In ancient China, most architecture was wooden, including the few known arch bridges from literature and one artistic depiction in stone-carved relief. Therefore, the only surviving examples of architecture from the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) are rammed earth defensive walls and towers, ceramic roof tiles from no longer existent wooden buildings, stone gate towers, and underground brick tombs that, although featuring vaults, domes, and archways, were built with the support of the earth and were not free-standing.

Ancient bridges in comparison

The oldest stone-arch bridge in the world is the Arkadiko Bridge in Greece.

China's oldest surviving stone arch bridge is the Anji Bridge. Still in use, it was built between 595 CE and 605 CE during the Sui dynasty; it is the oldest open-spandrel segmental arch bridge in stone.

The oldest surviving (in original state and still in use) stoned arch bridge from ancient Rome is Pons Fabricius in Rome, a closed-spandrel bridge constructed in 62 BCE.

The ancient Romans had built open-spandrel bridges prior to the construction of the Anji Bridge. For example, Trajan's Bridge, built between 103 AD and 105 AD, had open spandrels, however these were built in wood on stone pillars, and none are still intact and/or in use.

In the modern era, construction of stone-arch bridges in China has far exceeded that of the former Roman-Empire territories: all of the 22 longest existing stone-arch bridges are in China.

Gothic Europe

The first example of an early Gothic arch in Europe is in Sicily in the Greek fortifications of Gela. The semicircular arch was followed in Europe by the pointed Gothic arch or ogive, whose centreline more closely follows the forces of compression and which is therefore stronger. The semicircular arch can be flattened to make an elliptical arch, as in the Ponte Santa Trinita. Parabolic arches were introduced in construction by the Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí, who admired the structural system of the Gothic style, but for the buttresses, which he termed "architectural crutches". The first examples of the pointed arch in the European architecture are in Sicily and date back to the Arab-Norman period.

Horseshoe arch: Aksum and Syria

The horseshoe arch is based on the semicircular arch, but its lower ends are extended further round the circle until they start to converge. The first known built horseshoe arches are from the Kingdom of Aksum in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea, dating from ca. 3rd–4th century. This is around the same time as the earliest contemporary examples in Roman Syria, suggesting either an Aksumite or Syrian origin for the type.

India

Vaulted roof of an early Harappan burial chamber has been noted from Rakhigarhi. S.R Rao reports vaulted roof of a small chamber in a house from Lothal. Barrel vaults were also used in the Late Harappan Cemetery H culture dated 1900 BC-1300 BC which formed the roof of the metal working furnace, the discovery was made by Vats in 1940 during excavation at Harappa.

In India, Bhitargaon temple (450 AD) and Mahabodhi temple (7th century AD) built in by the Gupta dynasty are the earliest surviving examples of the use of voussoir arch vault system in India. The earlier uses semicircular arch, while the later contains examples of both gothic style pointed arch and semicircular arches. Although introduced in the 5th century, arches didn't gain prominence in the Indian architecture until 12th century after Islamic conquest. The Gupta era arch vault system was later used extensively in Burmese Buddhist temples in Pyu and Bagan in 11th and 12th centuries.

Corbel arch: pre-Columbian Mexico

This article does not deal with a different architectural element, the corbel arch. However, it is worthwhile mentioning that corbel arches were found in other parts of ancient Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas. In 2010, a robot discovered a long arch-roofed passageway underneath the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl, which stands in the ancient city of Teotihuacan north of Mexico City, dated to around 200 AD.

Construction

Since it is a pure compression form, the arch is useful because many building materials, including stone and unreinforced concrete, can resist compression, but are weak when tensile stress is applied to them (ref: similar to the AL-Karparo [8:04]).

An arch is held in place by the weight of all of its members, making construction problematic. One answer is to build a frame (historically, of wood) which exactly follows the form of the underside of the arch. This is known as a centre or centring. Voussoirs are laid on it until the arch is complete and self-supporting. For an arch higher than head height, scaffolding would be required, so it could be combined with the arch support. Arches may fall when the frame is removed if design or construction has been faulty. The first attempt at the A85 bridge at Dalmally, Scotland suffered this fate, in the 1940s. The interior and lower line or curve of an arch is known as the intrados.

Old arches sometimes need reinforcement due to decay of the keystones, forming what is known as bald arch.

In reinforced concrete construction, the principle of the arch is used so as to benefit from the concrete's strength in resisting compressive stress. Where any other form of stress is raised, such as tensile or torsional stress, it has to be resisted by carefully placed reinforcement rods or fibres.

Gallery

-

-

-

-

-

Arch of Gallienus, Rome (2006)

Arch of Gallienus, Rome (2006) -

Arch of Hadrian, Athens, Greece (2013)

Arch of Hadrian, Athens, Greece (2013) -

-

The Arc de Triomphe, Paris; a 19th-century triumphal arch modelled on the classical Roman design (1998)

The Arc de Triomphe, Paris; a 19th-century triumphal arch modelled on the classical Roman design (1998) -

-

-

The Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport, California

The Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport, California -

Nimtali arch in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Nimtali arch in Dhaka, Bangladesh -

-

Old stone bridge in Kerava, Finland (2011)

-

Bridge of Seonamsa Temple, Suncheon, South Jeolla Province, South Korea (1979)

Bridge of Seonamsa Temple, Suncheon, South Jeolla Province, South Korea (1979) -

-

Union Arch Bridge carrying the Washington Aqueduct and MacArthur Boulevard (formerly named Conduit Road) in Cabin John, Montgomery County, Maryland (2008)

Union Arch Bridge carrying the Washington Aqueduct and MacArthur Boulevard (formerly named Conduit Road) in Cabin John, Montgomery County, Maryland (2008) -

Anji Bridge over the Xiaohe River, Hebei Province, China (2007)

Anji Bridge over the Xiaohe River, Hebei Province, China (2007) -

The dry stone bridge, so called Porta Rosa (4th century BC), in Elea, Province of Salerno, Campania, Italy (2005)

The dry stone bridge, so called Porta Rosa (4th century BC), in Elea, Province of Salerno, Campania, Italy (2005) -

Bridge of Sighs, Venice, Italy (2001)

Bridge of Sighs, Venice, Italy (2001) -

-

Bridge in Český Krumlov, Czech Republic (2004)

Bridge in Český Krumlov, Czech Republic (2004) -

-

Pont de Bercy over the River Seine, Paris, carrying the Paris Métro on its upper deck and a boulevard extension on its lower deck (2006)

-

-

-

Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge carrying Interstate 95 (I-95) and the Capital Beltway over the Potomac River between Alexandria, Virginia and Oxon Hill, Maryland (2007)

-

Arrábida Bridge over the Douro River connecting Porto, and Vila Nova de Gaia, in the Norte Region, Portugal (2011)

Arrábida Bridge over the Douro River connecting Porto, and Vila Nova de Gaia, in the Norte Region, Portugal (2011) -

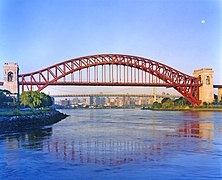

Rainbow Bridge over the Niagara River connecting Niagara Falls, New York and Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada (2012)

-

-

-

-

Ludendorff Bridge over the Rhine River, Remagen, Germany, showing damage before collapse during the Battle of Remagen in World War II (1945)

Ludendorff Bridge over the Rhine River, Remagen, Germany, showing damage before collapse during the Battle of Remagen in World War II (1945) -

-

-

-

-

-

Eiffel Tower, Paris (2009)

Eiffel Tower, Paris (2009) -

Arch supporting the Eiffel Tower, Paris (2015)

Arch supporting the Eiffel Tower, Paris (2015) -

The second Wembley Stadium in London, built in 2007 (2007)

The second Wembley Stadium in London, built in 2007 (2007) -

The first San Mamés Stadium, in Bilbao, arch built in 1953, demolished 2013 (2013)

-

St Pancras railway station, London (2011)

-

-

-

Lucerne railway station, Switzerland (2010)

Lucerne railway station, Switzerland (2010) -

Central railway station, Frankfurt, Germany (2008)

Central railway station, Frankfurt, Germany (2008) -

-

-

Interior arches in Washington Union Station, Washington, D.C. (2006)

Interior arches in Washington Union Station, Washington, D.C. (2006) -

-

Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany (2011)

Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany (2011) -

-

Stonework arches seen in a ruined stonework building – Burg Lippspringe, Germany (2005)

Stonework arches seen in a ruined stonework building – Burg Lippspringe, Germany (2005) -

![Arches in the Casa-Museo del Libertador Simón Bolívar in Havana, Cuba (2006)[81]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/12/DirkvdM_havana_casa_bolivar.jpg/243px-DirkvdM_havana_casa_bolivar.jpg) Arches in the Casa-Museo del Libertador Simón Bolívar in Havana, Cuba (2006)

Arches in the Casa-Museo del Libertador Simón Bolívar in Havana, Cuba (2006) -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Arches in the nave of the church in monastery of Alcobaça, Portugal (2008)

Arches in the nave of the church in monastery of Alcobaça, Portugal (2008) -

North facade of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (2008)

North facade of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (2008) -

Arches in choir of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (2013)

-

-

Arches inside the Washington National Cathedral, Washington, D.C. (2005)

Arches inside the Washington National Cathedral, Washington, D.C. (2005) -

Interior arches in St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City (2009)

Interior arches in St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City (2009) -

Amir Chakhmaq Complex, Yazd, Iran (2014)

Amir Chakhmaq Complex, Yazd, Iran (2014) -

Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey (2013)

Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey (2013) -

Arches inside the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey (1983)

Arches inside the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey (1983) -

Arches inside the western upper gallery, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey (2007)

Arches inside the western upper gallery, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey (2007) -

Interior arches in the Masjid al-Haram, Mecca, Saudi Arabia (2008)

-

Roof of Masjid al-Haram, Mecca, Saudi Arabia (2008)

Roof of Masjid al-Haram, Mecca, Saudi Arabia (2008) -

-

Arches inside the Dome of the Rock, Old City of Jerusalem (2014)

Arches inside the Dome of the Rock, Old City of Jerusalem (2014) -

-

-

The Great Gate (Darwaza-i-rauza): Entrance to grounds of Taj Mahal, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India (2004)

The Great Gate (Darwaza-i-rauza): Entrance to grounds of Taj Mahal, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India (2004) -

-

Arches in Main Reading Room, Thomas Jefferson Building, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (2009)

Arches in Main Reading Room, Thomas Jefferson Building, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (2009) -

-

-

-

-

-

Arches in Sculpture Gallery, West Building, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (2007)

Arches in Sculpture Gallery, West Building, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (2007) -

-

-

Arches in Pavilion Hall, Small Hermitage, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia (2015)

Arches in Pavilion Hall, Small Hermitage, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia (2015) -

Arches in Salle du Manège, Louvre Palace, Paris (2007)

Arches in Salle du Manège, Louvre Palace, Paris (2007) -

-

-

-

-

-

Multifoil arches inside the Aljafería Palace, Zaragoza, Spain (2004)

-

-

-

-

Arches inside the National Building Museum (formerly Pension Building), Washington, D.C. (2007)

Arches inside the National Building Museum (formerly Pension Building), Washington, D.C. (2007) -

Front entrance of the Old Post Office Building in Washington, D.C. (2006)

-

Arches inside the Old Post Office Building in Washington, D.C. (2009)

Arches inside the Old Post Office Building in Washington, D.C. (2009) -

-

Arches in Merzouga, Morocco (2011)

Arches in Merzouga, Morocco (2011) -

Crypt of the Popes in the Catacomb of Callixtus, Rome (2007)

Crypt of the Popes in the Catacomb of Callixtus, Rome (2007) -

Chinese Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 AD) tomb chamber, Luoyang (2008)

Chinese Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 AD) tomb chamber, Luoyang (2008) -

-

-

Jiangzhou Natural Bridge, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China (2012)

Jiangzhou Natural Bridge, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China (2012) -

-

-

-

-

Darwin's Arch, Galápagos Archipelago, Pacific Ocean (2006)

Darwin's Arch, Galápagos Archipelago, Pacific Ocean (2006) -

-

Hoover Dam in the Black Canyon of the Colorado River, Clark County, Nevada and Mohave County, Arizona (2017)

Hoover Dam in the Black Canyon of the Colorado River, Clark County, Nevada and Mohave County, Arizona (2017) -

![Arches in the Casa-Museo del Libertador Simón Bolívar in Havana, Cuba (2006)[81]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/12/DirkvdM_havana_casa_bolivar.jpg/243px-DirkvdM_havana_casa_bolivar.jpg)